Fiction II

13th Summer

It Was So Hot and dry the summer I turned thirteen, that bumblebees dropped dead mid-flight, but the upper floors of my father’s house were caverns, cool, shaded, invaded by the smell of wet moss.

That August, my mother had gone to Youngstown, Ohio. By Greyhound. Her high school reunion and a visit with her brother and sisters. She hugged me at the station and whispered, Don’t come back changed again. A Methodist, in theory, that is, she didn’t like Pentecostals, theoretical or otherwise. Holier-Than-Thou’s. That’s what she called them. My father was one of Them. My father and my mother had been divorced for eleven years. Mary was also one of Them. She and my father had been married for ten and a half years. Mary was exactly that much older than my father.

Whenever I leaned out those upper windows on those evenings to listen to tambourines and voices coming from my father’s modest church at the end of the block, my elbows and the undersides of my arms always looked afflicted, a crazy collage of gray splinters and rubbery green paint. As if his place were melting. The tambourines called to mind 1001 Arabian Nights. I liked to fix my eyes on the lights streaming through the windows of the church and imagine that the sanctified sisters, black, white, and colors in between, were dancing the dervish, barefoot, garbed in gauze and bells, whirling, bejeweled navels set in quivering bellies, smudged eyelids closed, the glint of teeth slipping through parted lips. In reality, they were mostly bare-faced, outfitted in generous housedresses or knitted suits that clung too snugly, and yes, some bellies did quiver. From that same window, I could also hear the wife and husband team of Sister Anne and Brother Arnie. They shouted into microphones, and their voices, Tennessee-touched and immediate, levitated above the organ music and handclapping and then evaporated into the varnished rafters.

I don’t remember their last name now. But I do remember that they dispatched dented yellow school buses to neighborhoods all over the city on Sunday mornings to swoop up us kids, mainly poor, mainly black, for Bible school, bribing us with free Clark Bars so ancient that the chocolate had begun to turn white in places.

It’s Sunday morning. Ten days before Mom leaves for Youngstown. I’m up early. I’m going to catch the yellow bus. The snores coming from her room assure me that she won’t hear me stealing away. Most of the kids are still dressed in Saturday play clothes dotted red with spilled Kool-Aid and smudged brown with melted bits of Klondike bars, but I’m wearing the very best from my closet, a lavender organza dress, matching patent leather pumps with Cuban heels, and white lace socks. It’s last year’s Easter outfit.

I’m real cute, I think, even though I’m carrying my perpetual cluster of Kleenex. I’m on my way to be healed of the hay fever that gets worse spring, even though we’re well into summer. Mom calls me Blossoms. No, I don’t think it’s so funny, but it’s a good name, because the little buds of tissue, white and pink and mint green like after-dinner mints at cashier counters, bloom from every pocket and shirt sleeve and waistband in my closet. If they made scented Kleenex, Mom always jokes, I’d buy those for you so you’d at least smell like a flower.

On this morning I figure my dad has paid enough in time and tithes to make my healing possible. My face, pretty, they say, in winter and autumn, is puffy, huge with congestion. In spite of what they say, I‘m really ugly now. Cabbage Patch Doll ugly. Mommy’ll kill me when she finds out. She’ll think I went to the other side. The HolyRoller side. Against her. To Dad and Mary’s side. But in my mind, a miracle is worth more than anything she can do to me., and anyway, it’s usually nothing stronger than her elbow in my ribs, or index and middle knuckles working the bone at the back of my head.

The bus finally stops with a shudder in front of the one-story brick church. Dad and Mary are there to meet me, even though I didn’t tell them I was coming. Mary looks sick. Her brown-yellow face is ashy. Her legs and fingers are sausage-like and her breathing is loud as her chest rises and falls.

I’m here, I announce. My teeth are gritty with chocolate and nougat, but I smile anyway.

Mary’s all cheeks and teeth behind the veil of that black hat of hers. The bottom half of her face is smiling. The top half isn’t. My dad gathers me up in his arms and kisses the top of my head. He smells good, like canned pineapple in heavy syrup. I tell them that I’m here for a healing. That I’ll be a believer if I can walk away from their church breathing freely and looking winter-time pretty.

Gloria, Mary wheezes, That’s not the way the Lord works. Not the way He works, Missy.

Missy . . . Mary and me? Truthfully? It’s a cold war between us. Her style is indirect. She always makes mean comments about Mom — about her temper, her strictness and — Wouldn’t it be nice, Mary always asks afterward, If you would come and live with us? She only invites me when Mom and I have been fighting. But that’s how Mary is, Mom says when she gets all worked up, Not filled with any damn Holy Spirit, but with her holy tricks, and that she, Mom, will drop dead and go to hell before she lets Mary get her hands on me.

The Lord, my dad continues, Doesn’t have to prove a thing to you, sweetheart.

He don’t have to bribe a soul, Missy. Not a soul.

My left hand’s squeezing a sticky Kleenex, but I unfurl the fingers of my right hand and show them the crumpled Clark Bar wrappers.

She steps forward and lifts the veil. She does all the talking after that. She says faith has to come first. I want to know how there can be faith if there’s nothing to base it on. She says, That’s what faith is, Gloria. Belief. Belief without question. Without doubt. The fingers on the hand that’s not holding the Bible flutter at her chest as she stops to catch her breath. Without thought, she continues after a few seconds pass. If you were half as smart as you and your dad think you are — she looks at him — you’d know that. She exhales through pursed lips, releasing the aroma of Sen-Sen, and then she moves closer. The hardest heart to believe, she whispers, Is a heart hardened by Satan.

I don’t believe in Satan, so I’m not convinced, but I look to my dad anyway. Pretending to wave to someone who’s not even looking his way, he turns his back on the tension between me, his first and only child, and Mary.

The music begins. Creepy Bela Lugosi organ chords. People speaking in tongues. The Holy Spirit’s language. Others are thrown from chairs, fully possessed by what they call The Spirit. One of them is my dad. By now my scalp’s twitching because I’m embarrassed to see him so vulnerable to something I can’t touch and don’t understand. Mary is crying hard. And coughing harder. Tears of delight, she calls them. For a moment I’m all alone, the only person in the whole place not possessed by anyone but herself. I try to tremble, but can’t. I try to beat myself to tears by imagining Mom and Dad never getting together again but that doesn’t do anything, either. I just can’t catch the Spirit.

After a while a line forms. The healing line. Some are in wheelchairs, maybe paralyzed, and some are leaning on crutches with missing rubber tips, or bracing themselves on borrowed crutches that are too long or too short. Moms holding their babies at face level. Just like on Sunday morning TV. Mary pulls me from my folding chair even though I don’t want to stand.

Go on. Go and accept the Lord into your heart.

Brother Arnie and Sister Anne rattle on in tongues and call to Heaven while their middle daughter launches three-fingered chords from the keyboard. People rise from wheelchairs or let crutches fall away. The organ lightens, turns joyful, and the handicapped dance to the music, palms and faces turned upward as if testing for rain. Their eyes are closed, but that doesn’t stop them from weaving in and out of rows without falling or even stumbling. It’s something that always amazes me. It’s all so much like a movie. Sun stationed outside the stained glass window. People standing in its many-colored rays looking very celestial. And for a moment, it could be Heaven. It really could.

My turn. Sister Anne, hair rolled away from her school principal’s face, addresses the congregation.

Brother Duke’s girl is with us today to finally accept Jesus Christ as her Lord and Savior.

No, I say too loudly. I have hay fever. I’m here to get a healing.

The organ pipes up. Two-handed and full-bodied chords are everywhere in me. Knocking in my head. Bouncing off my ribs. Pulling at my tongue. Brother Arnie stands large in front of us, Goliath, stoning the congregation with sanctified laughter while he rocks from front to back. That’s when I hear it. The guitar. My Dad’s. He’s at the lip of the pulpit plugged in to his amplifier, picking a melody that counters the organ’s. Sister Anne grabs my shoulder with one hand. Sister Anne presses her weight into my forehead with the heel of her other.

Do you accept the Lord Jesus as your personal savior?

Yes, I lie, remembering the garden of Kleenex on the floor all around my bed. When I throw my hands into the air like the others, flinging the pink petals high, a woman behind me catches The Spirit. She whoops and hollers. She has The Spirit. I am jealous. Sister Anne presses harder. Her wrist is flattening my stuffy nose. Her hand is a heating pad. Her pulse is a jackhammer, and I’m sure she’s trying to push me to the floor.

In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, I command you, Satan, out of this child and ask you, Lord, to send your healing spirit to her this morning. Heal, she commands. Heal, she moans.

She’s pushing with a mighty force now, but I won’t fall. I am Mom’s girl through and through, so her temper’s rising high and fast in me. If I don’t get the real thing, The Real Spirit, I won’t go down. No. Uh-uh. Not on your life.

I stand there, bracing myself against Sister Anne’s righteous vengeance. No spirit. No rapture. No instant healing. Brother Arnie says God bless you. I’m breathing completely through my mouth by now, so every breath is a pig snort. I try to say thank you, but my throat is clogged with mucous, so my words bubble forward, but they’re not the Spirit’s words. Sister Anne gives me a hearty squeeze and moves me along quickly. Too quickly. My dad, still at the pulpit, still playing, is smiling, is pleased, though nothing miraculous has happened. I go back to my seat.

You’ve been saved, Mary says.

Saved from what, Mary?

She pokes my chest. She means yourself. That I’ve been saved from myself.

I look back at my dad. Still strumming, still humming.

Later in the evening, I’m home again. Mom’s not inside watching the Pirates-Cardinals playoff game. No. She’s on the porch. Waiting for me. Her arms cross her chest umpire-style. I know I’m in trouble. She’s humming. I know I’m in deep trouble. I tell her I’ve been saved.

Saved from what, fool? she asks.

Myself, I answer, thinking of Mary. Myself.

You might be saved from yourself, she laughs, But all the saving in the world won’t help your hard, sorry ass now.

Poor, sorry me. Hard heart . . . Hard ass . . . I’m waiting for the elbow, but her arms don’t uncross.

I’ll tell you right now, I wasn’t worried about you. You don’t think I know that you snuck off to your father’s? She removes her baseball cap and drags it across her forehead. Y’all are just hell-bent on making me old and ugly before my time, you and your father.

I’m waiting for the knuckle now. I tell her she probably won’t have to spend so much money on Kleenex and nose spray. When she slaps me, I give my other cheek, but she just laughs and cries at the same time and then banishes me to my room for the summer. The rest of June. And July, including the 4th . Blistering August, too. Fine with me. But I don’t tell her that.

On the first day, I read my Bible, the one with the white leatherette cover, with color pictures of miracles. His words in red. I bask in rebirth, wait for my miracle and only pretend to swallow the decongestants Mom leaves on my bed.

On the second day, nothing, so I smash Smokey Robinson & The Miracles ooh ooh ooh baby baby so that Armageddon won’t catch unclean music seeping from my soul.

It’s the third day now, and something does happen. A mini-miracle. Not the one I’m expecting, though. I win Mom’s pity. My bedroom’s sweltering. Because the cord spits a small fireworks display just before the fan’s blades stop turning, Mom, standing on the other side of my bedroom door, says, Come on out of there, Gloria.

But it’s a short miracle. I’m not allowed to venture any further than our front porch, so I sit on the steps in the evenings, waiting for the sun to swipe its trail of orange and blue across the clouds, watching fireflies come from nowhere and then disappear into the hedges, smashing ants with the heel of my sandal, pretending not to see my friends.

Mister Softee’s bell. I see his dirty white truck rolling slowly down our street. It’s decorated with curling decals of Popsicles, Klondikes, ice cream sandwiches and triple banana splits. Old Stoneface, Mom, sits on the porch, too. She’s watching me from the corner of her eye. I can tell that her heart is growing sweeter for me than ice cream. And just as soft.

On the fourth day, friends ask me to skate and Double Dutch. I look to the ground and refuse, not letting on that I’m under house arrest, but telling them, instead, that I’ve been saved and reborn.

Saved by who, girl?

By The Spirit, of course.

So what’s it saving you from?

Dirty dancing. Double Dutch. I don’t do those things anymore.

But as I watch them, I can’t keep my feet from moving to jump rope routines that I create in my head. I can’t stand it when Barbara-Ann wins the praise that’s normally mine. That’s when I lower my head so that she and Mom don’t see me cry.

On the fifth day bumble bees, bullies this time of year, aren’t even bothering with me. I’m more stuffy than ever, and the rosebush she planted for herself two years ago on Mother’s Day seems to grow at a crazy rate, its trailers reaching out from our garden to the steps where I sit. I am not healed.

By the seventh day, disappointed, I tell myself I never really believed. I unsave myself by declaring it out loud three times in front of my vanity mirror. Then, I retrieve my skate key and jump rope from the trash can near the bedroom door, and when I play Little Anthony & The Imperials’ “Tears On My Pillow” pain in my heart over you-ooh- ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh ooh-ooh-ooh as loud as both of us can stand it, Mom opens the door and stands in the threshold, lip-synching while I slow drag with some imaginary boy. Four days later, she’s off to Ohio. And I’m with Dad again. For two weeks this time.

It’s unbearable, the heat. Maybe worse than last summer. I hear my dad’s voice in the next room, a powerful tenor, sometimes muted, sometimes choked. It’s merging with the distant organ and tambourines as he dresses for evening service. The guitar waits by the door downstairs. My favorite. The acoustic one with the abalone fret board and twelve steel strings. It’ll go to church with him this evening, but I won’t. Earlier in the day I picked a blues tune by ear.

You’ve inherited my ear, he told me, But Muddy Waters is not my taste. Not the Lord’s, either. Then he smiled in spite of himself.

The bedroom door’s ajar. Grainy breathing, then a gurgle. I’m in. He’s fully dressed. His eyes are red. He’s been crying for her. Mary .Bloated flesh. Devilish thoughts about Mary float in and out of my head. My dad has no idea of the way his daughter’s mind works.

Mary is wearing him down, just like I knew she would, Mom always says. Old bitches are like that, Gloria. They drink a man dry.

Seven medicine bottles on the nightstand near the bed. The largest Bible I’ve ever seen. Not like my pretty white one, but a black archive of magic and pestilence and poetry. They’re waiting for the Lord to heal Mary, but I’m sure that she’s not long for this life. I’m beginning to fear her. It’s the water I hear sloshing around in her. It’s the way she says my name . . . Gloria . . . as if I’m a hymn or something . . . Gloria . . . as if she can, will, take me with her or something. I’ve never seen death before, and I’m sure Mom doesn’t know what’s going on here. When she says Mary is wearing him down, she has no idea.

I’m at the doorway when she pushes my name f rom her throat. Her eyes’re closed and her lids’re smooth and shiny as a doll’s, but her partially closed hand creeps through the air in my direction. The wedding band chokes her finger. Is it keeping the blood from her failing heart? Maybe she’s the one with the hardened heart. Marriage will kill you, Mom says. Marriage and hard-headed kids.

Come in, sweetheart, and sit near her, he says. She’s been asking for you.

I sit on the bed at the corner farthest from her, careful not to let any part of her touch me. I’m scared to death of death. The room. Covering my nose. Covering my mouth. Wondering if you can inhale death. Wondering if she’s really dying or just plain very sick. Seeing shadows around Dad’s eyes. I move closer, taking my chances, letting my thigh touch the sheeted sole of her foot. I hate the way Dad tries to make us a family when we’re really not. It used to be Mary; now it’s him. But I’m only thirteen and, at this age, I suppose my father still melts something in me.

I’m carrying his guitar when we approach the church door. Dad’s wearing a new grey suit. Whiffs of Old Spice. Maybe Mennen. Me, I’m wearing old cutoff jeans, a halter top and no socks. Not dressed for church.

You’ll have to sit with her while I’m away, he says.

Is Mary going to die, Dad?

We’re all going to die, Gloria.

I mean, is she going to die, I soften my voice, Soon?

You know, sweetheart, Mary loves you in her own way.

This night is a little cooler than last night, only eighty-seven degrees at eight o’clock. Stars are brighter and clearer, sometimes looking like they’ve been hung in the black sky by some careful decorator, sometimes looking like they’re nowhere in particular. I like this feeling of no-beginning no-end that the sky gives, and how the stars make a fool of my eyes.

Your mother still holding out hope for the Pirates?

As always.

Of course. You know, your aunt Gwen and her boyfriend, husband now, me and your mother, we doubled up for our prom. Your mother and Gwen, he continues, Look enough alike to be twins.

We rest on the curb about thirty feet from his church. The light stains our skin ocher. Eighty-seven degrees is starting to turn prickly. Tiny electrical bites all over me. Haloing Dad’s head and mine, gnats charge and collide with one another. Dad’s face relaxes. Sitting down and looking beyond the street and at the river makes conversation easier for him, I think.

Your mother could have made more of herself than she has. She had a thing for music. She got pretty good on the guitar, too, at one time, except when it comes to singing she can’t carry a tune in her own hands. He looks at me and laughs.

Looking at the river, too, I tell him that I like tambourines but that organs make my skin crawl. Too many horror movies, I guess.

She had an eye for design, too. You should have seen our first place. Modest. You know? One tiny room and a kitchenette. She created something from almost nothing. Touches here, touches there.

I think about our house. Mine and Mom’s. It’s clean, neat, nice, really, but . . . I wouldn’t go as far as saying she’ll win Decorator of the Year. A comment, I think, a blind man would make. Someone blinded by love, maybe? I have a pain — no, maybe ache is a better word — yes, a dull ache in my chest. I don’t know why, but I’m sure he has one in his, too.

I would bring your mother flowers, he goes on, And do you know what she’d do with them? She’d put water in a glass bowl, a shallow one, remove the petals from some of the roses, always roses, and arrange the petals on the saucer.

Like a kaleidoscope?

There you go. Just like a kaleidoscope. And there they were, floating in water, but holding their shape. Beautiful. Disconnected from their source yet holding on to their beauty and form. Beautiful . . .

Beautiful, he says. His voice disintegrates. It returns as a chuckle. When he begins to remember something so pleasant and so private, he turns silent. Again. For a long time, it seems.

So, how is your mother?

Fine. Mmm. She sends her love, I say, before I know what I’m saying.

My dad doesn’t say anything. I have the feeling he knows I’m lying but hopes I’m not. He smiles quickly and rolls his eyes upward, saying, Sure she does. But he believes. I know he does.

People are filing into church now. When he turns his head away from them, quickly, I turn, too. He notices. We laugh together, leaning into each other.

There was a time, he says, releasing the guitar from its hard-shell case, when your old man was a regular guy with a regular life.

I know, Dad, but I don’t remember.

Your mother and me, we won our share of jitterbug contests. Did she ever show you the pictures? She must still have them.

The thought of my father throwing my mother over his head or through his legs, so funny, but I don’t think this is the right time to laugh. I want to say, yes, right before she shredded them with her teeth and bare hands and flushed the pieces down the toilet after I’d found them in her cedar chest and told her I wanted to come and live with you.

No, she never saw them. Did you and Mary ever jitterbug?

No. He removes a marbled pick from his shirt pocket. Once I met Mary, the only dancing I did after that was for the Lord. Your dad, he says, as though he were someone else, Was a pretty good sprinter, too.

I know. And swimmer. And student. I’ve seen the scrapbook. Remember? In other words — and I try to speak gently — My Dad could have made more of his life, too.

He tilts his head and looks at me. He swats a stray gnat. He begins to play. It’s not a spiritual. It’s not a hymn. Not even a mildly sacred song. It’s a ballad that builds, like a bubble of water at the end of a faucet, just hanging there, and then bursts and finally trickles, chord by chord, into a slow leak. The name of it escapes me, but I hum along anyway. I’ve heard it . . . where? Radio? Movies? I don’t know.

Is your mother seeing anyone?

Like dating?

I guess that’s what I mean.

Nah.

Think she’ll ever marry again?

She keeps saying if she meets the right man. You know her. He’s got to love the Pirates, whoever he is.

Sometimes, my father says, The right man comes along at the wrong time.

But if he comes along at the wrong time, how can he be right?

That’s when my Dad stops playing. He ruffles my hair. He palms my head as if it were a basketball, or as if I am a son and not a daughter, and then pushes it away.

Sometimes, he says, It’s the right man, but the woman’s mind is in the wrong place.

Oh, I say, not sure of what he means and trying not to think beyond his explanation but wondering if Mom will ever bring her mind back to the right place.

His tune begins again. Then someone slams the church door. He asks me to sing along. Though I, too, have a fine voice, I say no, because I’m too shy to let mine loose in the shadow of his. I just listen. I love my father’s voice, with or without the guitar. I wish I could describe it. I can only say it’s . . . it’s kind of . . . I guess, haunting. Not scary-haunting like organs, but nagging, sad-haunting. My eyes are closed by the time I finally stop thinking. My heart is beating too fast. My stomach is turning.

He isn’t singing words now. Just sounds. Cries. Tongue-clicks. Laughs. Not quite radio blues. Maybe church blues. Maybe a Dad-trying-to-be-like-the-Lord blues. Maybe unchurch blues. A Dad-thinking-about-a-Mom blues. Maybe both coming from the same place. And I know that if he doesn’t ease up, let up soon, that my throat will start to close and the blood will start to pump in my head and my lip will start to twist in a way that I can’t control and I’ll—

I made a mistake, he says, not really to me and not to himself, either. He just says it.

Something, I believe, is turning over in his heart, something that stretches, snorts, kicks up dust and dead leaves and insects. I’m quiet, because I don’t know if it’s something true and deep, or if he’s feeling the weight of Mary’s sickness and wishes he could be somewhere or someone else. I feel grownup suddenly, afraid for myself to be grownup, afraid for him if he’s feeling something true and deep, and disappointed in him if he can’t take the weight.

How about a short walk? he asks.

I grunt and he interprets it as no.

You used to like those foot-long hot dogs. How about it? Relish? Mustard? Remember?

No thanks, I say. Let’s just stay right here. It’s nice. Tell me about our first Christmas.

The strumming. He looks. His head’s cocked to the side, which gives him the attitude of a younger man, a street-wise man, and not that of my dad. I don’t like it. But when his face catches and holds the headlights of an approaching car, I see that he’s smiling. I like it.

Your first Christmas, he repeats.

Our first Christmas. The three of us, I say boldly. Me. You. Mom.

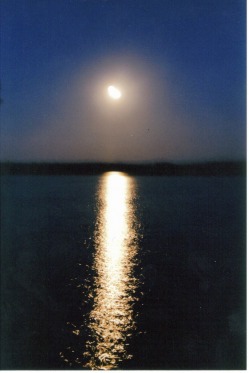

His fingers resting on the strings. Lightly. An arpeggio. And he begins — Once upon a time — looking beyond gnats and lamp post, beyond church and docked barges, and to our left, where the Monongahela runs along broken railroad tracks and smoking steel mills, telling our story not to me but, instead, dumping memories on the pleated face of a white moon that lounges on the slick black waters. More than an hour passes. I feel so . . . I don’t know. Melancholy?

The telephone rings. My father and I, barefoot, are and eating Owl’s Potato Chips. On the third ring he motions for me to answer.

It’s Mom.

-- When are you coming back? I ask. I cover my mouth to keep the words between only us. I think Dad still loves you, I whisper, before I know what I’m doing. He looks at the sky a lot.

I wait for her to say something. She sucks her teeth. Why does she have to be so hard?

-- Mom, I continue to gush, I can’t wait until you come back. It’s so, so heavy here. Thick. You can spoon it up. You don’t know.

Before I can tell her about Mary, she says, Put your father on. Her voice is flat but, at the same time, full of purpose.

-- Are you mad at me? What did I do now?

-- No, I’m not mad at you. You’re my . . . my Blossom-Baby. Now, put your father on.

She sounds strangely tender. It gives me chills.

When Dad picks up the extension, she says, Hang up, Gloria. I pretend to by pushing down on the button, but the handset stays at my ear. My breathing is low and controlled.

-- Gloria and I were talking about you last night.

-- That must have been some hellified conversation.

-- How’re Gwen and Ed?

-- Gwen and Ed are fine. I’m fine. Everyone’s fine, fine, fine.

I have to sneeze real bad, so I mash the handset into the flesh of my thigh. The sneeze is a closed-mouth one, so everything that’s trying to escape is forced to stay. I hold my nose and blow. The inside of my head crackles so loud that I miss some conversation.

-- to stay on six months . . . at least.

-- Youngstown must be some town.

It sure must be, I think, so loud, in fact, that I have the feeling I’ve actually said it. I cover the mouthpiece and await my discovery.

-- You remember Lamar Jefferson. He went to school with us.

-- Mmm.

-- He was at the reunion. I spent a lot of time with him. He says hello. I told him I’d tell ell you if I saw you.

-- I remember Lamar’s second wife. Ruby.

-- He’s a widow, now.

-- Again? Sweet Jesus! Two strikes. Down on his luck.

-- Luck can change.

-- What about Gloria? You know, she was in the wishing well again. Asking for stories again.

The wishing well? Is he nuts? He was the one splashing around, gazing at the sky and all, talking about jitterbugging, wishing for old times, wishing—

-- You always wanted to take her from me. You and Mary. I was never a good enough mother, never a good enough this and that and—

-- That’s a lie.

-- If you say so. Anyway, I need time to make up my mind.

-- About?

-- About Lamar.

I want to hang up so that I can’t hear any more, but at the same time I want to know more without hearing it. I hear Mary calling, so one ear’s on the phone and the other’s straining toward he stairs. I want to hear Dad tell Mom about Mary and how this is probably not the best place for me to be right now and how a girl should be with her mother and father together no matter what and can this Lamarwhateverhisnameis be more important than her own child, but all I hear are their breaths and my own and Mary calling Gloria . . . Gloria . . . in a way that makes me so angry I slam down the handset, not caring if they know I’ve been listening.

I’m upstairs. Trying to calm myself. Trying not to think evil of the nearly dead. Thinking how I’d like to put a pillow over Mary’s face and finish her off. Trying to picture this Lamarwhateverhisnameis and Mom with that stupid too-small Pirates baseball cap of hers on her head and Dad squeezing memories from his guitar.

Mary’s sitting up in bed when I enter the room, looking tired but, to my surprise, stronger.

What’s the matter, Gloria?

Nothing. It’s time for your medicine I say, but she reaches across to the nightstand and pushes all the bottles toward the trash can.

It wouldn’t be so bad, you know.

What? I bend to pick up bottles.

Wouldn’t it be nice, she says, If you could come and live with us?

By now I’m under the bed pretending to look for the pills. It’s a safe place, under the bed, a place where I can think for a moment. More thinking. More wishing well. Thoughts and questions roll away from me. They roll towards me. They’re as hard to stop or catch hold of as Mary’s scattered pills.

What are you doing under there, Gloria?

Bed springs creak as she rolls over.

Come sit near me a while.

I’m wishing, I shout, meaning to say thinking. Do you mind?

Don’t wish. Don’t even think. Just trust. Have faith.

The smell of wet moss is gone. The room is dry. I hear my father’s footsteps. I hear the organ. I hear tambourines, like sleigh bells, entering the room through the open windows. When I see my Dad’s feet, I think I might leave the shade of the bed. I might run past him. I might grab the guitar. I might go with him this time. Again. In a real way. Would it be so bad?

It was that summer night when I was thirteen that I finally sang with my father.

Because their room had turned so dry, the insides of my throat and nose were parched, and when I finally found the never to sing with him, our first duet for Mary was a long song without words. It was the same one he’d sung for me on the night before we sat near the church, when the slick black waters of the Monongahela captured the pleated face of the white moon. From that night and for eight years more, we continued on in that way. No lyrics. Only sounds.

# # #